In a joint statement with the Namibian Government, the German Government has officially recognised the genocide against the Herero and Nama, 117 years after German forces carried it out. The statement says that Germany has agreed to pay Namibia $1.35bn in a gesture of reconciliation.

“The Aegis Trust welcomes Germany’s recognition of the genocide carried out by German forces against the Herero and Nama peoples in the first decade of the 20th Century,” says Chief Executive Dr James Smith. “Although the term ‘genocide’ was not coined or given legal force until the 1940s, it defines the atrocities to which the Herero and Nama were subjected, and as such the German government’s acknowledgment is an important step on the long road to healing and learning from the tragic past. In the same spirit, we urge Turkey to follow suit and acknowledge the Armenian Genocide carried out by the Ottoman Empire in the second decade of the 20th Century.”

The Herero-Nama Genocide: a short overview

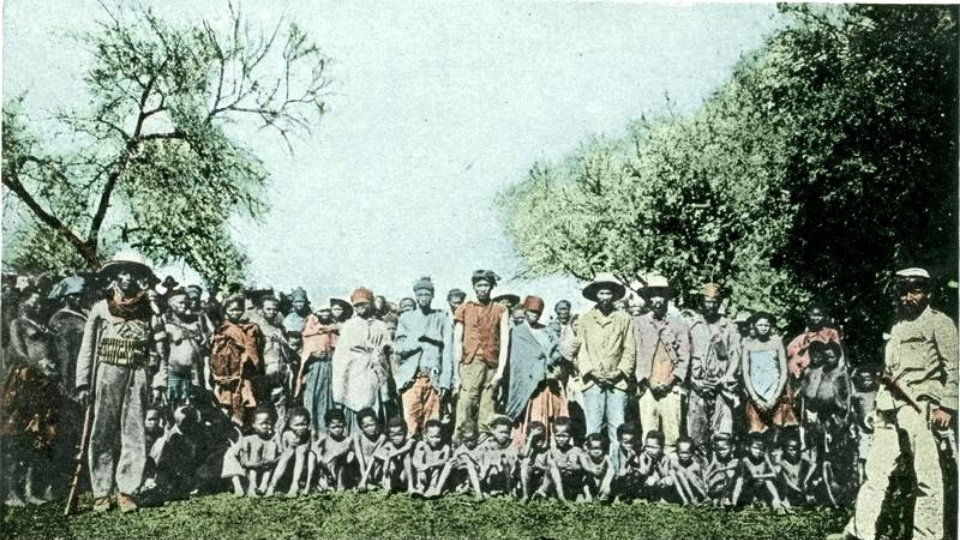

German settlers first arrived in South West Africa (Namibia) in the 1840s as missionaries and traders. Germany annexed South West Africa in 1884, and in 1894 sent troops to extend its rule.

Hereros attacked German forces in January 1904, on hearing they were to be forced onto reservations to make way for a new railroad. Lieutenant-General Lothar von Trotha arrived to suppress the rebellion. Herero warriors were driven out into the Kalahari desert, where the wells were systematically poisoned.

On 2 October 1904, von Trotha issued an order to the Schutztruppe (‘protection force’) to kill the remaining Herero. Herero women and children were driven into the Omaheke desert. They died of starvation and thirst. Others were sold into slavery, many as sex slaves – although Von Trotha opposed this, arguing the Herero insurrection was “the beginning of a racial struggle”.

Following orders from Berlin at the end of 1904 to accept surrendering Hereros, many of those who had survived to that point were interned in concentration camps. There they were often worked to death as slave labourers. Some were subjected to lethal medical experiments. Shootings and hangings were common. Disease also claimed many lives. At one of the most notorious camps, on Shark Island, only 20% of those interned survived. Female prisoners were forced to scrape the flesh from the skulls of dead inmates – which were then sold by their captors to institutions in Germany for pseudoscientific race science research.

By the time international public pressure led to the closure of the concentration camps in 1908, 65,000 Herero (80% of the Herero population) and 10,000 Nama (50% of the Nama population) had been murdered.

More than a century after their fertile lands were seized by German settlers, many of the descendants of the survivors live in poverty on the edge of the desert.

In 2011, Herero skulls still held in German museums and institutions were finally returned to Namibia for burial. There was, however, no formal apology or reparations from Germany for the families of victims of this first genocide of the 20th Century. Until now.